Slaveri i Oman

Oman var under lång tid en knutpunkt och ett regionalt centrum för den indiskoceanska slavhandeln, där slavar skeppades från Afrika till Persien och till övriga Arabiska halvön. Slaveriet förbjöds efter den brittiskstödda statskuppen 1970, då en konservativ monark avsattes av en mer framstegsvänlig monark. Många afroomanier härstammar från de slavar som transporterades till området under slavtiden.

Historik

Oman och Zanzibar

På 1200-talet beskriver Ibn al-Mujawir att det fanns både afrikanska och indiska slavar i Jemen och Oman, av vilka indier såldes för högre priser än afrikaner.[1]

Oman var förenad med Zanzibar 1692-1856, och slavhandeln i Zanzibar gick från Zanzibar till Oman och vidare till Persien och Arabiska halvön. Riket delades 1856 i sultanatet Zanzibar (1856-1964) och Muskat och Oman (1856-1970), men Oman fortsatte vara en knutpunkt för den indiskoceanska slavhandeln. Slavhandeln hämmades av Moresby Treaty 1822.

Slavhandeln i Zanzibar avskaffades formellt 1876. I praktiken fortsatte dock slavhandeln från Afrika till Arabiska halvön och Persien med Oman som knutpunkt. Rutterna lades dock om i slutet av 1800-talet.

En amerikansk resenärs beskrivning av slavarna i Oman på 1860-talet beskriver nästan alla som afrikaner, men nämner enstaka icke afrikanska slavar, så som att sonen till en ämbetsman var son till en slavinna från Georgien.[2]

En slavhandel pågick under 1900-talet med barn som kidnappades eller köptes av sina föräldrar från Sudan och Etiopien till Jeddah och Mecka. En annan pågick med människor från Afrika och Fjärran Östern, som följde med pilgrimer på pilgrimsfärd till Mecka och som såldes på slavmarknaden vid framkomsten. En del av dessa slavar importerades från Saudiarabien till Oman.

Oman

Oman liksom Gulfstaterna betraktades på 1920-talet som brittiska protektorat i vid mening. Muscat och Oman sågs som autonoma stater med särskilda förbindelser med britterna. Kontakterna mellan dessa stater och Storbritannien sköttes av India Office och deras utrikespolitik av Foreign Office, men den egentliga brittiska kontrollen var mycket bristfällig. India Office lade sig inte i inre affärer utan nöjde sig med att skydda brittiska medborgare, upprätthålla en hjälplig fred mellan härskarna och utåt försöka få det att verka som att de åtlydde samma brittiska internationella traktat som britterna lydde under.

Britterna bekämpade aktivt slaveri i hela det brittiska imperiet i enlighet med 1926 Slavery Convention. De var dock medvetna om att det vid samma tid pågick en aktiv slavhandel i Oman, som de dock inte ansåg sig ha möjlighet att ingripa mot, och agerade främst för att se till att denna inte blev internationellt uppmärksammad, snarare än att ingripa mot den.[3]

1935 meddelade britterna Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery att Oman och Muscat hade förbjudit slavhandeln, men vägrade att tillåta någon internationell insyn, eftersom det vid denna tid fortfarande i själva verket pågick en intensiv slavhandel i Oman, där slavar användes i pärlfiskeindustrin och uppges ha blivit ovanligt hårt behandlade.[4]

1936 uppgav britterna inför NF att Oman bara meddelade sig internationellt genom britterna. Rapporten medgav att det fortfarande förekom en slavhandel från Baluchistan och Saudiarabien till Oman och Qatar, men att denna var ytterst blygsam, och att de slavar som ville kunna söka asyl hos brittiska agenten i Sharjah.[5] I verkligheten bedöms de brittiska rapporterna ha varit långt ifrån sanningsenliga.[5]

Bertram Thomas beskrev slavinnor i Oman på 1930-talet:

- "Soon through the prison courtyard below came twenty young negresses, dancing asensuous measure, their heads poised in snake-like detachment balancing fullwater pitchers. Here was the Bathing Chorus, a recognized institution when theSultan or I was in residence, and the tank in the bathroom must needs bereplenished daily. As they filed past the doorway of my room they ceased to sing;a young one, confident in her youth and greatly daring, risks what may be almosta wink in my direction, for in their world of Dhufar, they were none of them better than they should be. On filing out each halts to turn and make obeisance."[1]

Flera planer framlades om att ingripa mot slavhandeln, men ingen bedömdes genomförbar. År 1940 rapporterades att en stor del av slavarna som skeppades över persiska gulfen var från Baluchistan, och hade sålt sig och sina barn själva för att undslippa svälten i hemlandet.[6] Baluchiska flickor skeppades 1943 via Gulfstaterna till Mecka där de såldes som konkubiner för 350-450$, sedan vita flickor inte längre gick att få tag på.[7]

Avskaffande

Sedan Indien år 1947 blivit självständigt tog Brittiska Foreign Office för första gången en påtaglig kontroll över Gulfstaterna och kom i position att på allvar ingripa mot slaveriet, särskilt som en större internationell närvaro i Gulfstaterna drog en större uppmärksamhet till dem.

FN förklarade slaveri som ett brott mot de mänskliga rättigheterna i FN:s deklaration om de mänskliga rättigheterna 1948. Anti-Slavery Society påpekade att det fanns en miljon slavar i Arabvärlden, vilket var ett brott både mot FN:s deklaration och 1926 Slavery Convention, och krävde en kommitté i FN.[8] FN bildade därför Ad Hoc Committee on Slavery, som företog en internationell undersökning som resulterade i Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery.[9] FN:s Ad Hoc Committee on Slavery inkluderade information om slaveriet i Oman i sin slutrapport 1951.

Slaveriet förbjöds officiellt i Oman 1970 efter en statskupp stödd av britterna, då den gamla härskaren avsattes och hans efterträdare utfärdade en mängd samhällsreformer, av vilka avskaffandet av slaveriet var ett.

Efter slaveriets avskaffandes anställdes fattiga migrantarbetare för samma typer av arbeten enligt Kafala-systemet, som har kritiserats för att vara en modern form av slaveri.

Referenser

- ^ [a b] Edward Harthorn Slavery in Oman and the Southern Arabian Peninsula: Travelers' Perspectives

- ^ William Gifford Palgrave, Narrative of a Year's Journey Through Central and Eastern Arabia (1862-1863) (Macmillan, 1866), 98

- ^ Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, s. 164-66

- ^ Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, s. 265-66

- ^ [a b] Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, s. 265-67

- ^ Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, s. 304-06

- ^ Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, s. 304-07

- ^ Miers 2003, s. 310

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 326

Media som används på denna webbplats

Capture of an Arab slave dhow by HMS “Penguin” off the Gulf of Aden.

“HMS Penguin in the Gulf of Aden” for the Illustrated London News 50 (19 June 1867): 648

The screw gun-vessel Penguin, under Lieutenant Commander E. St. John Garforth, on the East Indies station, has captured nine Arab dhows engaged in the slave trade of the east coast of Africa, during the last three years, and liberated a great number of slaves. On May 20, having returned from the Persian Gulf, where she had been occupied about a month, she observed off the Gulf of Aden a dhow, to which she gave chase, and, having captured her, found on board 216 slaves, chiefly boys and girls, closely stowed, and all bound for Muscat, in the Persian Gulf. The dhow was hauled alongside, and, the slaves having been taken on board the Penguin, the dhow was then cast adrift and a crew sent to cut away her masts and rigging; they finally set fire to her, as shown in our Illustration, from a sketch taken at the time. The Arab captain, although apparently dying from fever when he first came on board, quickly rallied under simple treatment, for which he was very thankful and seemed to appreciate a kindness which he had very likely least expected to receive at the hands of his captors. The next day he and his orew (about fifteen) were put on board another dhow boarded by the Penguin, which proved to be a legal trader bound for Maculla, in the Gulf. The liberated slaves while on board the Penguin were well-behaved and kind to each other, sharing everything which was given them. Some of the youngest were much emaciated, but most were healthy and in good condition. They were conveyed to Aden — a passage of three days — and there disembarked. This is the largest number of slaves liberated by the Penguin out of any one of the dhows she has taken on this station.

Författare/Upphovsman: Hervé Cozanet, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

An indian traditional boat in northeastern wind. The Bay of Bombay in the background.

Författare/Upphovsman: Colomb, Philip Howard, 1831-1899, Licens: No restrictions

Identifier: slavecatchingini00co (find matches)

Title: Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean

Year: 1873 (1870s)

Authors: Colomb, Philip Howard, 1831-1899

Subjects: Slave-trade

Publisher: London, Longmans, Green and co.

Contributing Library: Princeton Theological Seminary Library

Digitizing Sponsor: Princeton Theological Seminary Library

View Book Page: Book Viewer

About This Book: Catalog Entry

View All Images: All Images From Book

Click here to view book online to see this illustration in context in a browseable online version of this book.

Text Appearing Before Image:

ing, and relieve omselves fromconsidering a question to which no one has yet venturedto assign a fair side. In only one thing should thecaptured negro be placed differently as regards hisgovernment from the man-of-wars man. The latterstarts fit for freedom; the former should prove hisfitness and his desire, by purchasing it, before it canbecome his. But even while I write, I know we shall not look atmatters in this way; the very most we shall be preparedfor is the continuance of the present system in a newlocality. And then I sometimes think that the des-tinies of the East African negro will not, after all, comeinto our hands. There has grown up in the centre of Europe a powerwhose aims are wider and more distinct than those ofEngland. She has never shown herself frightened at aname, nor does she hesitate about embarking on acourse of policy whose end may be centuries distant.That power is second to us in material interest in EastAfrica. Already, we are told, she is looking thither as

Text Appearing After Image:

OCEAN Slave trading waters of the 40 longttide East from Ga:eenwuii_ Edw^* We) ler, Luha Hfid-lion -Squarr Zcnd£<n J^nqrrui^i^ A Cs FINIS. 503 to a field worthy of her enterprise ; it is to be hoped weare either ready to do and dare, or to give place,should the time come, to anyone ready to take up thequestion at the point where we have left it. The termination of my visit to Zanzibar was alsothe end of my slave-catching experiences. Theygrew more sad as time drew on, and I see the changeis visible in what I have written. LONDON : PnlNTED BY SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE AND rAULIAJlENT STllEET 39 Pateenosteb Eow, E.G.LoxDON: November 1872. GENERAL LIST OF WORKS PUBLISHED BY Messrs. LOI&MAIS, &KEEI, EEADEE, and DTEE. AuTS, Manttfactuees, &e 13 AsTHONOiiry, Meteohology, Popl^lab GrEOGBAPHY, &C 8 BlOGEAPHICAI, WoEKS 4 Chemistby, Medicine, Suegeey, and the Allied Sciences 11 Ceiticism, Philosophy, Polity, &c.... 5 Pine Aets and Illitsteated Editions 12Hi

Note About Images

Författare/Upphovsman: Internet Archive Book Images, Licens: No restrictions

Identifier: slavecatchingini00co (find matches)

Title: Slave-catching in the Indian Ocean

Year: 1873 (1870s)

Authors: Colomb, Philip Howard, 1831-1899

Subjects: Slave-trade

Publisher: London, Longmans, Green and co.

Contributing Library: Princeton Theological Seminary Library

Digitizing Sponsor: Princeton Theological Seminary Library

View Book Page: Book Viewer

About This Book: Catalog Entry

View All Images: All Images From Book

Click here to view book online to see this illustration in context in a browseable online version of this book.

Text Appearing Before Image:

terwards displays. So that we generally understand that the stoppage of food is the simple and only way of dealing discipline to the rescued slave as we find him. We have heard something of late, of the beauty of the East Africans from the Lake District. I cannot doubt that if an average specimen of these Africans could be placed suddenly, just as he or she appears asa rescued slave, plump, well fed and cared for, on a London platform, there would be a cry of What a frightful object! If, however, the audience were prepared beforehand,the object would no longer be frightful but one to be certainly pitied—perhaps admired. No one knows better than the naval officer, how absolutely comparative beauty is. He falls in love with a face in a distant colony, and wonders at himself when he sees the same face in a London drawing-room. Therefore, although we may charge upon some writers a neglect of remembering the English idea of beauty when speaking of the Lake District negro, we must allow for the absence

Text Appearing After Image:

J^ m GALLA SLAVES on board HMS Daphne. From a photograph by Capt. Sulivan R.N. 273 of such standard when they write, and the strange sentiment which surrounds the subject. If we take the English ideal of beauty, the Galla slaves exported from Brava, much more nearly approach it than the negro farther south. Burton says that the Galla slaves are a sort of low-class Abyssinian in appearance;he further declares that they fetch low prices, being considered roguish and treacherous. I have no knowledge of the Abyssinian physique,but the few Gallas I had on board were of a much higher type than the more southern negroes, and more-over, according to all appearances, the Arab slave merchant set especial store by them. They certainly held themselves many degrees above their fellow captives—would not eat with them, formed a little clique of their own, and kept altogether aloof from the rest.There was one young girl, tall, slight, and by comparison not ill-formed or favoured, who wore some shreds of a spangled veil about her head. She was quite a lady negress, a

Note About Images

Författare/Upphovsman: Runehelmet derived from Aliesin, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

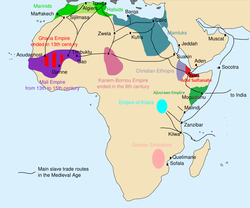

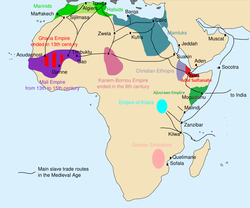

Slave trade in medieval Africa